World

Monkeys Know Who Will Win US Election 2024. Here’s How

Pennsylvania:

As Election Day looms with Kamala Harris and Donald Trump locked in a dead heat, pollsters and pundits are scrambling for clues to predict the outcome.

But what if the answer lies not in political data or campaign strategies, but in the instincts of a primitive part of the human brain?

New research I conducted with rhesus macaque monkeys suggests that when it comes to decisions like voting, people are not nearly as rational as they would like to believe.

It’s easy to associate instinctual reactions – like the fight-or-flight response or reflexively pulling away from a hot surface – with the primitive motive for survival. But humans also have a rational brain that can gather and weigh evidence, deliberating thoughtfully rather than relying on knee-jerk reactions. Why that rational brain seems to be hijacked by primitive instincts in situations where rationality would serve people better is one of the many reasons my neuroscience colleagues and I have been studying rhesus macaques for the past 25 years.

These monkeys are remarkably similar to people genetically, physiologically and behaviorally. These similarities have allowed researchers to make incredible medical breakthroughs, including the development of vaccines for polio, HIV/AIDS and COVID-19, as well as deep brain stimulation treatment for Parkinson’s disease and other neurological disorders.

My research on candidate preference is part of an overall focus on enhancing scientists’ understanding of the ability to interact effectively with others and to navigate social conflicts, the neural circuits that support it and how these circuits can deteriorate due to disease or external factors like inequality – all to better support those affected by these challenges.

Power of first impressions

Previous research revealed that human adults and preschoolers alike can accurately predict election outcomes after quick exposure to candidate photos. Plenty of evidence supports the idea that our primitive brain drives us to quickly form first impressions based on physical appearance – it was key to survival, after all.

But researchers don’t yet understand why this bias persists. New research with rhesus macaques has provided some answers.

In the study, which is under review at the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, we showed monkeys pairs of candidate photos from U.S. gubernatorial and senatorial elections, and they correctly predicted the outcomes based solely on visual features.

Specifically, the monkeys spent more time looking at the loser than the winner. This “gaze bias” predicted not only the election outcomes but also the candidates’ vote share. Monkeys tended to look at the candidates with more masculine facial features – and these were the candidates more likely to win in the real elections. Jaw prominence had a direct relationship with vote share.

Previous research helps explain the monkeys’ gaze bias. When monkeys were shown pictures of unfamiliar but powerful male monkeys, they would only glance briefly at them, presumably because monkeys interpret staring as a sign of aggression. But their gaze lingered when shown a low-status male monkey or a female.

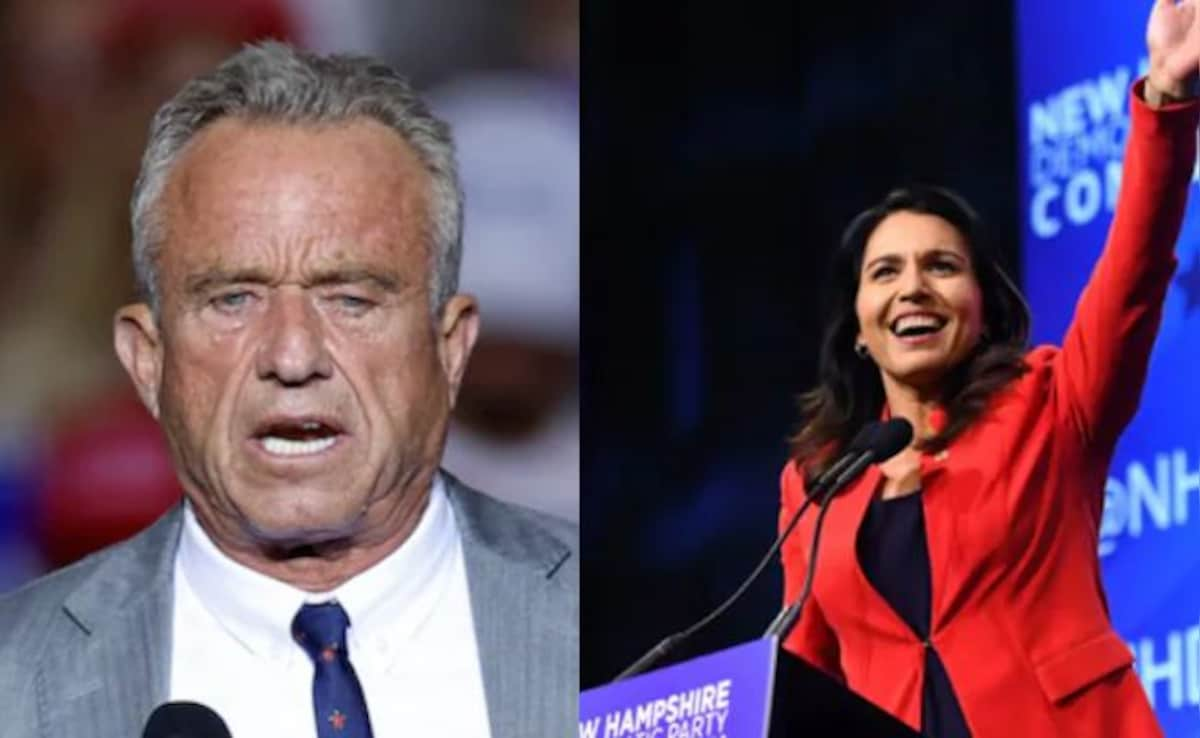

Those preferences were on full display when we showed the macaques photos from the most recent races involving Donald Trump. Their gaze bias, driven by primitive instincts, indicated the winners. The monkeys looked the longest at the Democratic opponent in the contest between Trump and Hillary Clinton. There was less of a gaze bias in the matchup with Joe Biden. And the monkeys looked for about the same amount of time at Trump as at Harris. That means among the three most recent Democratic candidates, based solely on visual features, the monkeys predicted Harris stands the best chance of winning against Trump.

An evolutionary hangover

Our findings suggest that voters instinctively react to cues of physical strength – cues that are equally evident to our monkey relatives. This “evolutionary hangover” illustrates how traits and behaviors that were once essential for survival persist even when they are no longer relevant.

The macaques’ ability to predict winners based on physical attributes alone challenges the notion that humans have evolved beyond superficial judgments in leadership selection. For those who pride themselves on rational decision-making, especially in vital decisions like voting, it’s a startling discovery.

Clearly people’s choices are not based solely on visual cues. But the evidence suggests that such factors could be more influential than you think. When you enter the voting booth, part of your brain might be drawing on ancient instincts, subconsciously evaluating who looks like they could best lead the tribe.

Staying rational, not primal

Raising awareness of these primal preferences is the first step in reducing their influence.

Political campaigns already tap into these instincts by highlighting a candidate’s physical strength and assertiveness. As voters, we can counteract their efforts by leaning into our rational brain’s capacity to understand and assess their policies and experience – something our primitive ancestors couldn’t do.

Techniques for choosing rationally rather than instinctively include exposing yourself to diverse perspectives, actively questioning your assumptions and considering the long-term outcomes of policies. Such deliberate steps toward making informed decisions take on new importance when you understand how your brain can be swayed at the ballot box by outdated preferences.

Of course, voters are not macaques. But the underlying instincts people share with our primate relatives could still subtly shape our decisions.

Acknowledging the role of these ancient cues can help people become more intentional in how they exercise their power in the voting booth. As democracy evolves, so too should humans’ understanding of how to engage with it.

(Author: Michael Platt, Professor of Marketing and Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Pennsylvania)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.