World

Child, 10, tells 911 dispatcher ‘I don’t want to die’ during school massacre

Calls from Khloie and others, along with body camera footage and surveillance videos from the May 24, 2022, shooting at Robb Elementary School, were included in a massive collection of audio and video recordings released by Uvalde city officials on Saturday after a prolonged legal fight.

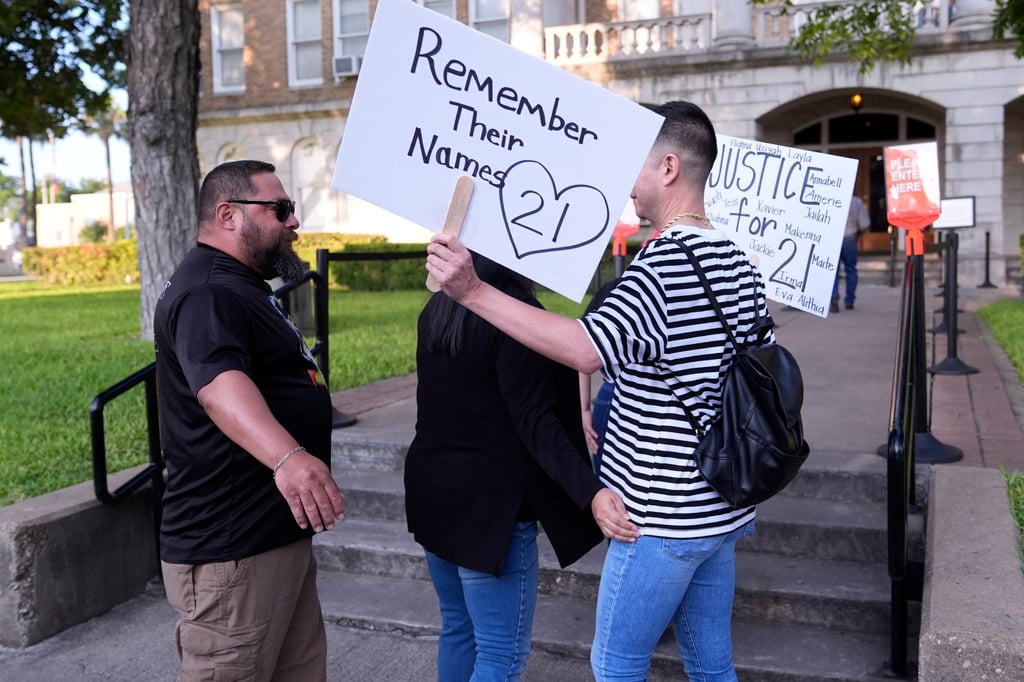

The Associated Press and other news organisations brought a lawsuit after the officials initially refused to publicly release the information. The massacre, which left 19 students and two teachers dead, was one of the worst school shootings in US history.

The delayed law enforcement response has been widely condemned as a massive failure. Nearly 400 officers waited more than 70 minutes before confronting the gunman in a classroom filled with dead and wounded children and teachers.

Families of the victims have long sought accountability for the slow police response in the South Texas city of about 15,000 people 130km (80 miles) west of San Antonio.

Brett Cross’ 10-year-old nephew, Uziyah Garcia, was among those killed. Cross, who was raising the boy as a son, was angered that relatives were not told the records were being released and that it took so long for them to be made public.

“If we thought we could get anything we wanted, we’d ask for a time machine to go back … and save our children, but we can’t, so all we are asking for is for justice, accountability and transparency, and they refuse to give this to us,” he said.

Jesse Rizo, whose nine-year-old niece Jacklyn Cazares was killed in the shooting, said the release of information on Saturday reignited festering anger because it shows “the waiting and waiting and waiting” of law enforcement.

“Perhaps if they were to have breached earlier, they would have saved some lives, including my niece’s,” he said.

The police response included nearly 150 US Border Patrol agents and 91 state police officials, as well as school and city police. While terrified students and teachers called 911 from inside classrooms, dozens of officers stood in the hallway trying to figure out what to do.

Desperate parents who had gathered outside the building pleaded with them to go in.

The gunman, 18-year-old Salvador Ramos, entered the school at 11:33am, first opening fire from the hallway, then going into two adjoining fourth-grade classrooms. The first responding officers arrived at the school minutes later. They approached the classrooms, but then retreated as Ramos opened fire.

At 12:06pm, much of the radio traffic from the Uvalde Police Department was still focused on setting up a perimeter around the school and controlling traffic in the area, as well as the logistics of keeping track of those who safely evacuated the building.

They have had trouble setting up a command post, one officer tells his colleagues, “because we need the bodies to keep the parents out”.

“They’re trying to push in,” he says.

At 12:16 pm, someone with the Texas Department of Public Safety, the state law enforcement agency, called police to let them know a SWAT team was on route from Austin, about 100km (162 miles) away. She asked for any information the police could give about the shooting, the suspect and the police response.

“Do you have a command post? Or where do you need our officers to go?” the caller asks.

The police representative responds that officers know there are several dead students inside the elementary school and others still hiding. Some of the survivors have been evacuated to a building nearby. She doesn’t know if a command post has been set up.

At 12:50 pm, a tactical team enters one of the classrooms and fatally shoots Ramos.

Among criticisms included in a US Justice Department report released earlier this year was that there was “no urgency” in establishing a command centre, creating confusion among police about who was in charge.

Multiple federal and state investigations have laid bare cascading problems in law enforcement training, communication, leadership and technology, and questioned whether officers prioritised their own lives over those of children and teachers.

Some of the 911 calls released were from terrified instructors. One described “a lot, a whole lot of gunshots”, while another sobbed into the phone as a dispatcher urged her to stay quiet. “Hurry, hurry, hurry, hurry!” the first teacher cried before hanging up.

Just before arriving at the school, Ramos shot and wounded his grandmother at her home. He then took a pickup from the home and drove to the school.

Ramos’ distraught uncle made several 911 calls begging to be put through so he could try to get his nephew to stop shooting.

“Everything I tell him, he does listen to me,” Armando Ramos said. “Maybe he could stand down or do something to turn himself in,” he added, his voice cracking.

He said his nephew, who had been with him at his house the night before, stayed with him in his bedroom all night, and told him that he was upset because his grandmother was “bugging” him.

“Oh my God, please, please, don’t do nothing stupid,” the man says on the call. “I think he’s shooting kids.”

But the offer arrived too late, coming just around the time that the shooting had ended and law enforcement officers killed Salvador Ramos.

Two of the responding officers now face criminal charges. Former Uvalde school Police Chief Pete Arredondo and former school officer Adrian Gonzales have pleaded not guilty to multiple charges of child abandonment and endangerment. A Texas state trooper in Uvalde who had been suspended was reinstated to his job earlier this month.

In an interview this week with CNN, Arredondo said he thinks he’s been “scapegoated” as the one to blame for the botched law enforcement response.

Some of the families have called for more officers to be charged and filed federal and state lawsuits against law enforcement, social media, online gaming companies, and the gun manufacturer that made the rifle the gunman used.