World

Iran president ‘has blood on his hands’: Ebrahim Raisi and Iran’s prison massacres

The Iranian presidency is considered a relatively weak post when compared to the country’s supreme leader. But there was a time in the late 1980s when Raisi had direct power over life and death.

Helicopter carrying Iran’s President Ebrahim Raisi has crashed

Iranian officials say a helicopter carrying President Ebrahim Raisi and Iran’s foreign minister went down in heavy fog.

First the guards canceled family visits. Then they confiscated the prisoners’ radios. Then came the tribunals.

Within weeks, 10,000 Iranian dissidents were dead.

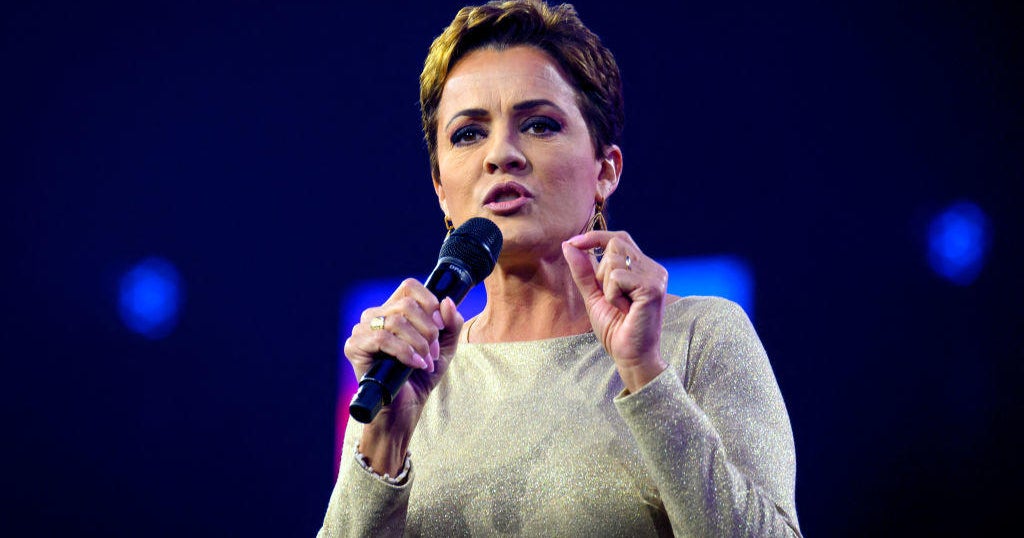

Sitting in judgment at some of these hastily called “death commissions” was a deputy prosecutor named Ebrahim Raisi, a hardline cleric who in 2021 was elected president of Iran. Raisi, 63, was killed Sunday when his helicopter crashed into a snowy mountainside near the Azerbaijan border.

While the Iranian presidency is considered a relatively weak post when compared to the powers invested in the country’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, there was a time in the late 1980s when Raisi had direct power over life and death.

He didn’t flinch.

“He definitely has blood on his hands,” said Mohamad Bazzi, director of the Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies at New York University.

As Iran comes to grips with the deaths of Raisi and Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian, the president’s demise highlights the pervasive control of hardline clerical rulers – and the lingering wounds of Iran’s Islamic revolution.

More: Helicopter carrying Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi crashes; massive search underway

New election, same old clerics

Now that Raisi is confirmed dead, the Iranian constitution calls for new elections within 50 days. But the outcome won’t matter in a theocratic democracy where candidates for office have to be cleared by the religious establishment, said Afshon Ostovar, an associate professor of national security studies at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif.

“Somebody else who the people don’t like, who the regime does like, will be elected,” Ostovar said.

Experts say the airtight dominance of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and his Revolutionary Guards guarantees that Raisi’s passing won’t bring Iranians any closer to justice for the decades of human rights abuses they’ve endured – including the 1988 prison massacres.

More: Iran launches dozens of drones at Israel, one injured in attack

Revolution, war and mass graves

Watch: Iranians gather in prayer to mourn President Raisi

A helicopter carrying the Iranian president, foreign minister and other officials crashed into a hillside. There were no survivors.

That summer, Iran was nearing the end of a ruinous eight-year war launched by its neighbor Iraq.

The prisons were packed with young leftists who’d been convicted for having links to an Iraq-based rebel group, the People’s Mujahedeen Organization of Iran, or Mujahedeen-e-Khalq. In July 1988, after the group launched an attack on Iran from its base in Iraq, Ayatollah Rouholla Khomeni, the Islamic Republic’s founding cleric, called for all PMOI prisoners to face special tribunals.

In a secret fatwa, Khomeni ordered officials to “annihilate the enemies of Islam immediately.”

“Suddenly there was word of fly-by-night, hastily conducted panels that lasted seconds, minutes, condemning these people to death,” said Elise Auerbach, an Iran expert at Amnesty International. Analysts believe around 10,000 people were executed in a matter of weeks in prisons across the country, their bodies hidden in unmarked mass graves.

More: An official appeared to say Iran’s ‘morality police’ would close. The truth is more thorny

Raisi: A ‘proud’ achievement

Raisi, working in Tehran, “was certainly one of the people responsible for ordering those executions,” Auerbach said.

The killings were so extreme that Khomeni’s deputy and preferred heir, Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, objected, saying the victims had already been legally convicted and sentenced. It made a mockery of the law, Montazeri argued, to impose the death sentence on people who were already serving their time and had committed no new crimes.

Raisi called the killings “one of the proud achievements” of Iran’s government, according to an Amnesty International report. He went on to serve as prosecutor general in Tehran and later as the top prosecutor in the country. More than three decades later, Iran still has not officially acknowledged the massacres, and families of the victims are forbidden to publicly mourn or commemorate their deaths.

In 1989, Montazeri released documents and a secret recording proving Khomeni’s role in the long-denied massacres. He was placed under house arrest. When Khomeni died in 1989, a lower-ranking cleric, Ali Khamenei, was named supreme leader

Remembered for a ‘bloodbath’

Khamenei is now 85, and the question of who might replace him has been complicated by Sunday’s crash.

“Raisi headed the list of potential successors,” Bazzi said. “Though it’s a little like papal succession, where the frontrunner going in isn’t necessarily the frontrunner at the end of the process.”

While Raisi’s presidency was marked by the violent suppression of women’s rights demonstrators, economic turmoil, and spiking conflict with the U.S. and Israel, he’ll probably be best remembered for one thing, Ostovar said: “This bloodbath of political prisoners at the end of the Iran-Iraq War.”