World

When does free speech cross the line into breaking U.S. anti-terrorism laws?

Charlotte Kates, a New Jersey native and Rutgers Law School graduate who co-founded the pro-Hamas organization Samidoun, has become the focus of an ongoing legal debate: When does free speech cross the line into breaking federal anti-terrorism laws?

Over the last year, Kates, who lives in Vancouver, British Columbia, said she met with mid-level leaders of at least two U.S.-designated terrorist organizations at a public conference in South Africa. She also joined members of the groups in online seminars in which they urged the audience to support Hamas and Hezbollah.

“The Palestinian resistance and the Lebanese resistance are not engaging in terrorism,” Kates told NBC News. “They’re engaging in a national liberation struggle.”

U.S. Treasury officials sanctioned her organization two weeks ago and declared it a “sham charity,” alleging that it was funneling money to a second, lesser-known U.S.-designated terrorist organization. At the same time, the Canadian government declared Samidoun a terrorist entity. Germany banned the organization last November, and Israel designated it a terrorist organization in 2021.

Republican members of Congress and several Jewish groups have petitioned the Justice Department, the FBI and other federal agencies to crack down on protest groups that openly praise terrorist organizations. Kates’ open support of terrorist organizations puts her in the middle of a growing legal dispute: When does free speech cross the line into breaking federal anti-terrorism laws?

FBI policy draws a distinction between protected speech and rhetoric that poses an immediate threat to public safety. The rules were enacted in response to decades of illegal surveillance and attempts to smear political groups by the FBI during the Civil Rights Movements and the Vietnam War era.

Spokespeople for both the FBI and the Justice Department said the agencies can neither confirm nor deny the existence of ongoing investigations. The FBI spokesperson added that the agency doesn’t open cases solely based on protected First Amendment activity.

Tom Petrowski, a former supervisory special agent and legal counsel with the FBI who led the Joint Terrorism Task Force in Dallas, is one of several former federal law enforcement officials who called for the Justice Department to launch a criminal investigation into Samidoun.

“The decision to open a counterterrorism investigation based on advocacy is usually a very difficult call,” Petrowski told NBC News. “In this case, it is not. The FBI would be derelict in its duty to not have a full investigation open on Samidoun.”

Petrowski argued that Kates’ advocacy for terrorist groups, coupled with her participation in webinars with members of Hamas, Hezbollah and Palestine Islamic Jihad, may have violated a U.S. law that bans working under the direction or coordination of U.S.-designated terrorist organizations while providing material support.

Civil rights attorneys and free speech advocates argue that the Constitution allows people to advocate for hate groups, including terrorist organizations.

David Goldberger, the former legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union who defended American Nazis in court when they petitioned to march through a Jewish community in Skokie, Illinois, in 1977, argued that the First Amendment protected Kates’ participation in the webinar.

Goldberger said Kates’ online appearance with members of Hamas and Hezbollah doesn’t mean the terrorist organizations are also helping coordinate Samidoun’s protests and teach-ins —which would violate federal anti-terrorism laws.

“What is the direct coordination? And to do what act?” he asked. “As far as I’m concerned, this is legitimate political advocacy, unpleasant as it may be.”

What is ‘knowingly’ coordinating with a terrorist organization?

Since its founding in the 2010s, Samidoun has mentored college activists across the U.S., held teach-ins, conducted letter writing campaigns on behalf of Palestinian prisoners and helped organize anti-Israel protests in New York, Chicago and elsewhere.

Kates, 44, defended her online appearances with members of Hamas, Hezbollah and other U.S.-designated terrorist groups in an interview. She argued that the designation process is unjust and that federal law enforcement wrongly stigmatizes Arab men.

In January, Kates joined an online panel with mid-level leaders of Hezbollah and Palestine Islamic Jihad — both U.S.-designated terrorist organizations. The video is still up on YouTube.

A few weeks later, she joined a Hamas official on a webinar in which they both praised Hamas’ attacks on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023. Kates introduced Basem Naim, a senior Hamas official, and said the two of them met at a pro-Palestinian conference in South Africa late last year along with representatives from Hezbollah and other U.S.-designated terrorist organizations.

Naim told the online audience that a needed front of Hamas’ war with Israel “is stripping the enemy of its international support.”

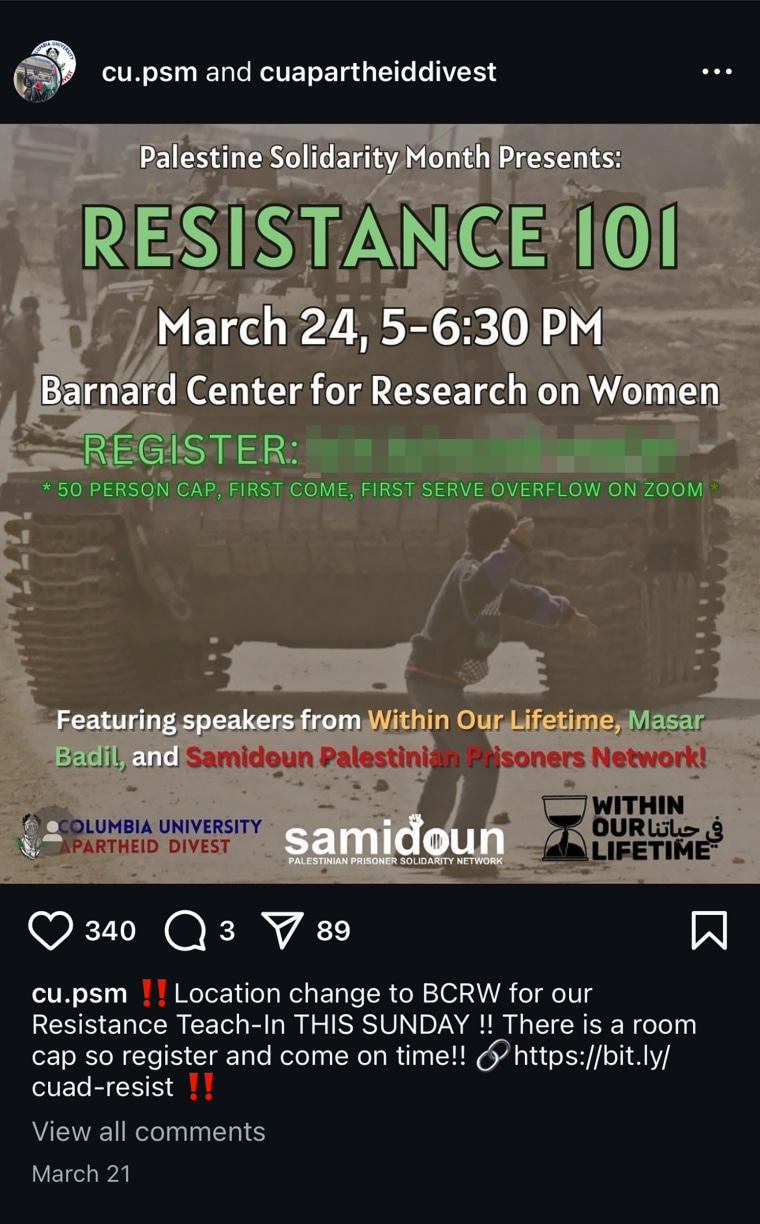

In March, Kates helped lead an online class for students at Columbia University and encouraged them to help build a mass movement to support armed resistance. “There is nothing wrong with being a member of Hamas,” Kates told the audience. “It’s important for us to come together to do everything that we can to make support for the resistance.”

Leaders of pro-Hamas protest groups, along with former federal law enforcement officials, all point to the same 2010 U.S. Supreme Court ruling when they’re asked about the legalities of Kates’ actions.

Months after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, Congress expanded material support for terrorism laws and banned knowingly giving a service to a terrorist organization, including expert advice or assistance that is “derived from scientific, technical or other specialized knowledge.”

People convicted of violating material support laws can face a maximum sentence of 20 years behind bars.

The Supreme Court ruling stemmed from a series of federal lawsuits filed by the Humanitarian Law Project, a nonprofit organization that wanted to lawfully train two U.S.-designated terrorist groups — the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam — in peaceful mediation tactics. The suits argued that material support laws are unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that “material support” for U.S.-designated terrorist groups as described in post-9/11 laws does extend to a narrow category of speech in which activists knowingly coordinate with terrorist organizations and don’t work independently of them.

“The statute is carefully drawn to cover only a narrow category of speech to, under the direction of, or in coordination with foreign groups that the speaker knows to be terrorist organizations,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the 2010 decision.

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, wrote that the material support law was unconstitutional because it punished “the communication and advocacy of political ideas and lawful means of achieving political ends.”

Kates cited the Humanitarian Law Project case to defend appearing in online panels with members of terrorist groups.

“We’re not taking direction from an organization by speaking alongside somebody at the event,” Kates said in the interview. “It’s important for more people to speak alongside the designated resistance organizations, to, again, break this taboo on political and moral support for the rights of Palestinians to liberate themselves by all means, including armed struggle.”

NBC News shared Samidoun’s events and activities with nearly a dozen former and current federal officials. Most said Kates’ appearances in webinars with members of U.S.-designated terrorist groups, along with telling college students there is nothing wrong with being a member of Hamas, is enough for the FBI to begin an investigation.

“It’s not so much like there’s a smoking gun, but rather it’s a totality of the circumstances,” said Frank Figliuzzi, a former FBI assistant director for counterintelligence. “Makes one question whether they are, indeed, an arm of these groups.”

Figliuzzi, now an NBC News contributor, added, “I think it’s a strong case to at least open it up.”

But Columbia Law Professor Daniel Richman, a former federal prosecutor, pointed to the Humanitarian Law Project ruling in discussing whether Samidoun’s webinars with Hamas and Hezbollah members would meet the standards of a successful prosecution.

“Then the question in that context is, is it a joint appearance, coordination?” Richman said. “Definitionally, there is some coordination, because we’re showing up at the same place.”

Richman argued that it isn’t clear whether Kates’ doing online panels with known members of terrorist groups would meet the standard for a criminal conviction. “It is not clear whether that skeletal coordination as to synchronization satisfies the standard for criminal liability,” he said.

On Oct. 15, the Treasury Department classified Samidoun as a “sham charity” that raises money for a lesser-known designated terrorist organization, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, or PFLP, whose attacks include blowing up a Swiss airliner in 1970 and assassinating the Israeli tourism minister in 2001.

Treasury officials also designated Kates’ husband, Khaled Barakat, as being a member of the PFLP and said he and Samidoun “play critical roles in external fundraising for the PFLP.”

Asked whether her husband was ever part of a terrorist group, Kates argued that Barakat was being vilified by “Zionist organizations” because “he is a very effective advocate for Palestine and for Palestinian liberation.”

Samidoun said on its website that it doesn’t have “any material or organizational ties” to U.S.-, Canadian- or European-designated terrorist organizations.

Building a material support case

After the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York, lawmakers passed a statute banning material support to terrorists that includes providing money or property. Then, after 9/11, Congress passed the Patriot Act, increasing federal law enforcement’s legal power to investigate people suspected of engaging in terrorism-related activities.

The Patriot Act also expanded the definition of “material support” to include providing “expert advice or assistance” to a terrorist group. And in 2010, the Supreme Court upheld the expansion.

Dubbed the “Brandenburg Test,” named after the 1969 Supreme Court ruling in Brandenburg v. Ohio, FBI policy says federal law enforcement can respond to advocacy that is likely and intended to “incite imminent lawless action.”

Petrowski argued that Kates’ appearing in a webinar with Naim, the Hamas official, who also appears in a Samidoun video on the website odysee.com, shows not only that Samidoun advocates on behalf of the terrorist organization but that it also has an ongoing relationship with its leadership.

On top of that, Treasury officials now say Samidoun helps raise money for the PFLP, he said.

“This designation demonstrates they are in open collaboration with Palestinian terrorists,” Petrowski said.

When NBC News asked about his relationship with Samidoun and Kates, Naim distanced himself. “I was only invited to one of their activities,” he wrote in an email.

The most aggressive step for the FBI would be to open a “full investigation,” which, according to FBI policy, has a high legal bar to clear and needs to include articulable facts that show that “activity constituting a federal crime or a threat to the national security has or may have occurred, is or may be occurring, or will or may occur.”

Full investigations that involve speech and other First Amendment issues require agents to get the green light from in-house FBI attorneys and federal prosecutors before they go to judges to request warrants, subpoenas or wiretaps, former agents said.

Lara Burns was the FBI agent who led the investigation into the Holy Land Foundation, a Texas-based charity that prosecutors said was raising money for Hamas. Five Palestinian American men who worked with the foundation were sentenced to prison for 15 to 65 years. Pro-Palestinian activists say the men were wrongfully convicted.

Burns, now the head of terrorism research at George Washington University’s Program on Extremism, said Samidoun should be under full investigation by the FBI. Burns pointed to the 2019 federal conviction of a Texas man who never committed violence but was convicted of conspiracy to provide material support after he spent years online advocating for the Islamic State terrorist group and lied to investigators about his activity.

“You have a right to speak your mind,” Burns said. “You don’t have a right to pick and choose which law to follow.”

Not all federal law enforcement experts agree with Burns’ approach. Barbara McQuade, the former U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan, suggested that the FBI conduct an “assessment.” McQuade said that would allow agents to recruit confidential informants and look into the actions of pro-Hamas groups without asking judges to sign off on investigative tools like wiretaps and warrants.

“This is where national security investigations become very challenging for investigators, but for good reason, because we don’t want people to be investigated merely because of their political speech, even if we find it to be repugnant,” said McQuade, now a legal analyst for NBC News. “So we want to look for actual direction and control. And I think that [Hamas] webinar comes really close.”