World

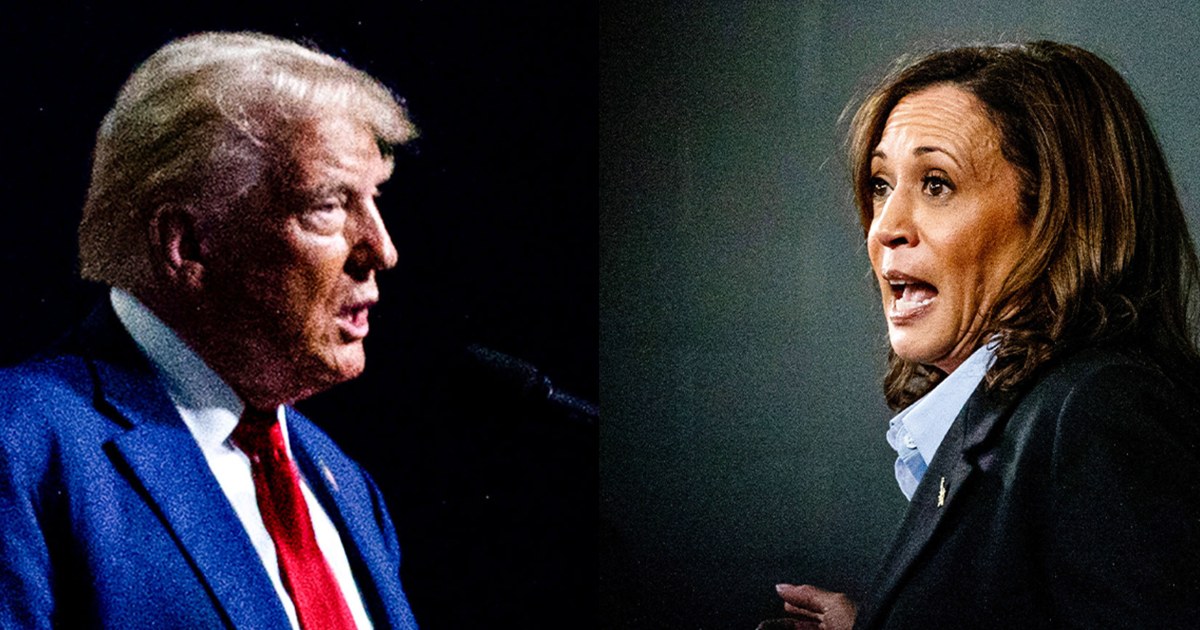

Who’s coaching Harris and Trump on foreign policy for Tuesday’s debate?

Foreign policy and national security have not played a dominant role in this year’s campaign so far, but a fumbled answer at Tuesday’s presidential debate could damage either candidate in a race with no margin for error.

As former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris head into the home stretch of debate preparation, who is coaching them on how to address the Israel-Hamas war, Russia’s onslaught against Ukraine and China’s efforts to overtake the U.S. as the world’s superpower?

There are stark differences between Harris and Trump in their foreign policy positions and how they express them. And the current and former officials and lawmakers who advise each candidate reflect those divergent outlooks.

In the mock debates Harris is holding in Pittsburgh as rehearsal for Tuesday, the adviser playing Trump’s role is underlining the differences between the candidates by allegedly dressing as Trump, right down to the big blue suit and long tie.

According to multiple sources associated with each candidate and their parties, here is a rough sketch of who is advising Trump and Harris on foreign policy for the debate — and for their potential presidencies:

Donald Trump

As always with Trump, expect his approach to be fluid and improvised, according to multiple sources and his own comments.

Trump has said that he has been prepping for the debate his whole life and questioned the need for elaborate study in advance. “I do, I have meetings on it,” Trump said recently when asked about his preparations. “We talk about it, but there’s not a lot you can do. Either you know your subject or not.”

Viewers can expect him to attack Harris over the southern border, the war in Gaza and the U.S. exit from Afghanistan. Trump has never articulated an overarching foreign policy, but he has one core belief that he has expressed for decades. Trump thinks other nations are taking advantage of the U.S. — that too many allies are freeloading off American military might and not spending enough on their own armed forces.

The former president’s campaign has no process for formulating foreign or domestic policy and Trump doesn’t have a designated foreign policy adviser. But his campaign team does provide talking points for surrogates on foreign policy.

Trump speaks about national security with a range of former officials who served in his administration and who are deemed loyal, as well as several senators. His son-in-law, Jared Kushner, retains influence as well. Trump’s emphasis on loyalty rules out a long list of former national security officials who worked under him but who have criticized him publicly.

The former Trump administration officials and senators who speak to the ex-president about foreign policy range from traditional conservative voices who invoke Ronald Reagan to those favoring a more isolationist “America First” vision that calls for scaling back international commitments and imposing tariffs on adversaries and allies alike. Some fall somewhere in between.

Many of these figures are jockeying for a job in a second Trump administration and trying to figure out how they can best play to Trump’s inclinations and opinions, said John Bolton, who served as Trump’s third national security adviser, said in an interview with NBC News.

Bolton, who advised Trump from 2018 to 2019, said that Trump has no coherent foreign policy views and that his “decisions are ad-hoc, anecdotal, transactional.” Bolton, who has publicly and repeatedly criticized his former boss, said he does not support either Trump or Harris.

Keith Kellogg, a retired Army general who served as Vice President Mike Pence’s national security adviser, has endorsed Trump’s “America First” rhetoric and founded a think tank bearing that slogan. Kellogg speaks to the former president regularly and has been advising Trump as he prepares for Tuesday’s debate, according to a source with knowledge of the matter.

Kellogg, who has defended the infamous phone call in which Trump asked Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy about investigating Joe Biden’s son Hunter, is co-author of a proposal to end the war in Ukraine. The plan calls for pushing Kyiv to negotiate with the Russians or face a cut in U.S. military aid, but would ramp up U.S. weapons deliveries to Ukraine if Moscow rebuffed peace talks.

Although many former advisers have fallen out of favor, Stephen Miller, who was a senior adviser and chief speech writer during Trump’s presidency, has been a consistent influence inside Trump’s circle for years. Miller has shaped Trump’s hard-line immigration policies and positions. If Trump is elected, Miller and Trump have vowed to launch a mass deportation of millions of undocumented immigrants.

Richard Grenell embodied the former president’s hostility toward European allies when he served as U.S. ambassador to Germany. Grenell backed withdrawing some U.S. troops from Germany due to what he called Berlin’s low levels of defense spending. He later worked as an envoy to the Balkans and as the acting director of national intelligence, where he ousted career intelligence officers.

Donald Trump Jr. has said Grenell is a “top contender” for secretary of state in a second Trump administration. Since Trump left the White House, Grenell has acted as an envoy for him abroad, meeting far-right leaders in foreign capitals.

Other former national security officials who have stayed in Trump’s orbit include Mike Pompeo, who served stints as his CIA director and secretary of state. Pompeo has shied away from MAGA-style isolationist rhetoric, expressing support for arming Ukraine, for NATO and for keeping a large U.S. footprint in the Middle East.

An unabashed hawk, he pushed for a tough approach to China and Iran while in the Trump administration, backing the U.S. drone strike that killed Iranian Gen. Qassem Soleimani.

Kash Patel worked on Trump’s National Security Council and in November 2020 became chief of staff to the acting defense secretary. Patel has embraced the former president’s calls to purge intelligence officials considered disloyal and promoted conspiracies hat the 2020 election was “stolen” and that a “deep state” inside the government is plotting against Trump.

JD Vance, the Ohio senator Trump picked as his running mate, has been a prominent voice in the Senate opposing military assistance to Ukraine. But multiple sources say Trump does not appear to rely on Vance for foreign policy advice.

Robert Lighthizer, a major influence on Trump’s trade policies when he served as the Trump administration’s trade representative, is urging more protectionism, extending tariffs on a range of products and countries.

The Republican lawmakers getting calls from Trump include Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas and Sen. Bill Hagerty of Tennessee.

Kamala Harris

Harris will likely criticize Trump for his praise of autocrats like Vladimir Putin and his skepticism about America’s longstanding network of alliances. Echoing past presidents from both parties, Harris views allies as vital to U.S. economic and military power — especially at a time when China and other U.S. foes are deepening ties with one another.

Harris relies mainly on her national security staff to help navigate foreign policy issues, and that advice has shaped how she talks about foreign policy as a candidate. But her White House staff is not legally permitted to take part in the preparations for the debate, so that will be handled by experts who are currently out of government.

Philippe Reines, who worked as an adviser to Hillary Clinton’s unsuccessful 2016 campaign against Trump, is playing the role of Trump in Harris’ mock debate sessions, just as he did in Clinton’s White House bid. The last time around, Reines famously adopted method-acting techniques and wore dress shoes with three-inch lifts and a loose-fitting suit with large cuffs and a long tie to try to help Clinton become accustomed to Trump’s large physical presence. Sources close to Harris say Reines will be wearing his Trump outfit again this year.

In an interview with NBC News, Reines recounted how he initially planned to read reams of material to prepare for the mock sessions.

“I got my own team of lawyers to volunteer to help because they’re so good with paper,” Reines said. “But then the paper overwhelmed me. Then I’m like, ‘F— this. Trump’s not reading any paper; I’m not going to read any paper. I rationalized it as, if I really get into character here, I’m not going to do anything he’s not.”

Colin Kahl, a former top Pentagon official in the Biden administration, said in an interview that he is informally advising the Harris campaign on foreign policy.

“Harris believes that foreign policy is a team sport, and so we need to rally our team,” said Kahl, who was also a national security adviser to Biden during Obama’s tenure. “Trump does not believe it’s a team sport. He’s also not sure which team he’s on.”

Other former national security officials advising the Harris campaign informally include Tom Donilon, who was Obama’s national security adviser; Jeremy Bash, chief of staff to former CIA Director and Defense Secretary Leon Panetta; and Tom Nides, a Democratic Party insider and former banker who served as the U.S. ambassador to Israel until last year.

Foreign policy questions debate prep will also involve Grace Landrieu, policy director for the Harris campaign and a veteran of Democratic politics, and Brian Nelson, former undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence at the Treasury Department. Nelson, who managed the imposition of sanctions against Russia, Hamas and other U.S. adversaries, has ties to Harris dating to her time as attorney general in California.

Harris’s White House staffers include Philip Gordon, her national security adviser. Gordon worked in previous Democratic administrations and has become an influential figure for Harris. He served as the head of European Affairs at the National Security Council under Bill Clinton, and as assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs during the Obama administration.

In a 2018 commentary that he co-wrote, Gordon said Russia’s aggressive actions had led him to conclude that the U.S. “needs to confront Russia more forcefully.”

In a 2020 book, Gordon recounted the fallout from U.S.-backed regime change in Iraq and elsewhere in the Muslim world. Gordon portrayed those efforts as unrealistic, uninformed and reckless.

Rebecca Lissner, Harris’ deputy national security adviser, taught at the U.S. Naval Institute and wrote a book about how to adapt American leadership to counter increasingly powerful authoritarian global powers led by China.

Dean Lieberman, Harris’ deputy national security adviser for strategic communications, crafts her speeches and public statements.

Harris’ speech at the annual Munich Security Conference in February, drafted by Leiberman, offered something close to the world view of the vice president — and her advisers — as well as a response to Trumpworld’s calls for pulling back from international commitments.

“History has also shown us: If we only look inward, we cannot defeat threats from outside; isolation is not insulation,” Harris said. “In fact, when America has isolated herself, threats have only grown.”